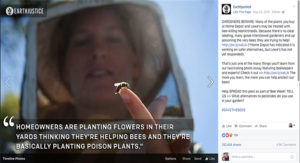

In the age of social media, misinformation spreads quickly, but proactive outreach can neutralize its effects.

You’ve seen the memes.

Bee-killing flowers treated with neonicotinoids. Unsafe, GMO-tainted food. An illegal workforce that burdens public resources while also stealing jobs.

In 1710, the Anglo-Irish satirist Jonathan Swift wrote, “Falsehood flies, and the truth comes limping after it.” But Swift never had to contend with the Internet age, where questionable information can circumscribe the globe in the blink of an eye.

“People are forming strong opinions with soundbites and 140-character Tweets,” said one industry veteran who has worked in sales and as a broker. “How do we combat misinformation that directly influences our industry?”

He has seen the negative effects on the nursery industry firsthand.

“Last year, we had a customer cancel their entire spring order because we said, yes, we do neonics,” he said. “Our reasons for doing so were justified. The other options available to do the same job are less safe. A neonic has a 12-hour re-entry. Everything else is 24 or 48 hours. You’re dealing with something that’s not only more toxic to the environment, but more toxic to the workers.”

The company applied the chemical after dark, when bees weren’t flying. They coordinated with a neighboring beekeeper to make sure the insects weren’t harmed. And they read research indicating that while neonics may contribute to bee deaths, the current science strongly suggests other causes at play, such as hive movement, lack of forage and the Varroa mite.

No matter.

“When you say pesticide, that’s what sticks in everyone’s mind, and it becomes the target,” he said. “It’s fear driven.”

The José they know

Fear is the number one culprit that Ali Noorani confronts on a daily basis.

The American-born son of Pakistani parents, Noorani serves as executive director of the National Immigration Forum in Washington D.C., an advocacy organization for the important role immigrants play in the American economy.

As with the use of pesticides, the role of immigrants in communities and the economy is more complex than can be captured in 140 characters. That’s why Noorani wrote a new book, There Goes the Neighborhood: How Communities Overcome Prejudice and Meet the Challenge of American Immigration, which will be published this month.

“The immigration debate really is more about culture and values than politics and policy,” Noorani said. “Your normal American, if you will, knows, respects and loves the José they know, but they’re terrified with the José they don’t know. And you can replace José with Mohammed, or any other immigrant.”

It’s commonly held by some that farm workers, if Hispanic, came to the United States illegally and are likely being paid under the table. They are often portrayed as violent criminals. Studies indicate that the born-here population is actually more likely to offend, but emotion often gets in the way of delivering the message.

“Those of use who care about immigration or immigrants are always making the mistake of having a policy debate when the rest of the country is having a cultural debate,” Noorani said. “It takes a strategy to cut through the misinformation. We have to be flexible and innovative.”

Noorani is best known for pulling together unlikely coalitions, including the Bibles, Badges and Business for Immigration Reform network, which combines faith, law enforcement and employers. The coalition has advocated for solutions that are compassionate, respect the rule of law and help grow the economy.

“We’ve done a good job of telling the story of an immigrant working at a nursery and what they’ve done to make a life,” Noorani said. “I think the story we’re not telling yet is the story of the (native-born) guy who delivers the plants in the morning. How does he view the guy that he works with? He’s a voice that people will trust because he is not one of the immigrants themselves.”

Turning down the volume on Internet posts, as well as responses, can help. Listening is vital.

“I think it’s very important to acknowledge the fear that people are feeling, then go from there,” Noorani said. “Social media has a tendency to jump right to the debate and forget there’s a person on the other side of the screen who really just wants to be heard.”

Debugging the myths

Karen Reardon serves as the vice president for public affairs at RISE (Responsible Industry for a Sound Environment).

RISE created a consumer-facing website called www.DebugTheMyths.com, which provides information on pesticides as well as fertilizers. “We are simply making sure we occupy all the spaces we can in the conversation,” she said.

RISE worked with the OAN to create a palm card that’s available to OAN members for distribution to their retail or wholesale customers. It provides basic facts on neonicotinoids. The organization also uses blogging and social media to provide factual information in plain language.

“When you’re looking at social media, there’s a proactive way to look at this,” Reardon said. “If you’re in the industry, you should be in the conversation and sharing good information, not responding in a reactive way. The goal is not to convince people who will not be convinced, but to share the good information that you have as a grower, because you’re the expert.”

Which is key.

“Take the time to have conversations with customers on social media or your Facebook page, so you become a trusted resource,” she said. “People are curious. They are not opposed to what you do. People are smart. They are just looking for good, balanced information to make a decision.”

Like Noorani, Reardon has created innovative partnerships to help spread positive and factual information. A recent example came on last year, when fear of the mosquito-borne Zika virus was spreading.

“There was enormous interest in clear information about pesticides,” she said.

Reardon knew that merely tapping into industry audiences she’d already cultivated wouldn’t allow her to reach the people she needed to reach. So, she began outreach to parenting blogs.

“We actually organized a Twitter party and were taking questions,” she said. “Parents had a lot of questions about it. No negative questions came up.”

Reardon sees great value in social media as a tool, even though it can be a double-edged sword.

“There’s no barrier to entry to share positive information,” she said. “We have to become very comfortable with the equalizing effects of the social media space. Everyone has an equal voice. There’s no reason not to be out there in a positive way.”

A modified understanding

The industry veteran mentioned earlier remembers a late-night skit on genetically modified organisms (GMOs) that appeared a few years ago on “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” (It’s on YouTube at http://tinyurl.com/gmo-skit.)

“They did a survey of people at a farmer’s market,” he said. “Everyone said ‘Yes, GMOs are bad.’ But when they asked what GMOs actually are, people didn’t have a clue.”

It’s an issue that Craig Regelbrugge follows closely in his role as vice president of AmericanHort, the national green industry association. He said that while nurseries don’t currently make extensive use of GMOs, they might in the future.

“It’s in our strong interest to ensure that we have all the tools in the toolkit,” he said. “If you consider the challenges facing humankind, with climate change, and you look at our cities, our cities possess anything but a native, nurturing environment. Plants are part of the solution to many of the ills that our society is struggling with.”

Why do GMOs matter in this?

“There are limits in terms of how effective traditional breeding can be at getting to a specific intended outcome,” he said. “We’re going to be talking about plants that have very specific attributes, such as pest resistance, or doing well in impacted soils, or salt tolerance. As techniques become faster and cheaper, we’re going to see a lot more interest.”

It makes sense for nurseries to take a proactive role in the discussion.

“So much of the debate has been forged around food, and stoking people’s fears about frankenfood and whatnot,” Regelbrugge said. “We go beyond food, and when you get beyond food, some of people’s perceptions are a little bit less troublesome.”

Joining the conversation

The principle holds true whether you are talking about pesticides, immigration, breeding or any other issue that might acquire a negative perception.

“You’ve got to be engaged in the conversation,” Reardon said. “If you’re not talking about what you do as a grower, someone else is, and they are filling that space without you. You’ve got a great story to tell. There is a vacuum out there created if you are not out there telling it.”

Regelbrugge recalled being asked by a friend to talk to a Tea Party group about immigration. He agreed as a favor.

“It was a great conversation,” he said. “We started with five or 10 farmers in the room who understood, five or 10 hard-liners who weren’t open to a conversation, and 60 people who had legitimate concerns and were willing to talk about solutions.”

Regelbrugge recognizes that immigration opponents have been successful at tapping into some people’s worst fears

and instincts. It is not a majority, but it’s been enough.

“The majority of people are supportive of reform, but they’re apprehensive about the details and they will never light the phones up,” he said.

His solution is to engage people in the great middle. That’s where the solutions are.

“I think the greatest success we’ve ultimately had is when people are willing to turn down the rhetoric and engage, listen and learn. I recognize that this is old school and maybe the world comes full circle, or maybe it doesn’t, but that’s where we’ve enjoyed the most of our success.”